Merely mentioning the VMax is sure to conjure images of a rear tire-roasting, muscle-bound, two-wheeled monster in the mind of just about any bike enthusiast old enough to recall the 1985 release of Mad Max.

And to this day the VMax retains much of its lore, even as a member of the Star Motorcycles brand.

A thorough and bold redesign of the VMax in 2009 – that included a massive boost in performance from its legendary V-4 engine – has not only stirred the souls of veteran riders, it’s also exposed a whole new generation of riders to the august Mr. Max.

|

Although Triumph’s Rocket III is a babe in the woods next to the long-running Max, it made an indelible mark on all of motorcycledom when unveiled in 2004.

Its massive, longitudinally mounted inline-Triple and three prominent exhaust headers were, and still are, striking. The Rocket has an imposing but approachable presence, as if it were a Boss Hoss Lite.

The Rocket, like the VMax, continues to thrill and intrigue since its birth.

However, unlike the VMax’s relative stagnation of design for 20-plus years, Triumph spawned a powerful, touring-capable cruiser, as well as a “classic” model, in the matter of only a few years from the original Rocket’s introduction.

For 2010, only six short years since the RIII was launched, the Roadster is with us. With this latest incarnation of the Rocket comes a breathed-on mill making this the most powerful Rocket III to date.

In many ways the Roadster and VMax are quite different. But the common denominator here, and the primary reason we brought them together, are the ridiculous amounts of horsepower and torque each produces.

Sure, modern literbikes like the BMW S1000RR are capable of more peak horsepower than the Rocket or Max; but good luck finding a production motorcycle engine that chugs out sizable hp numbers paralleled by plump torque figures like the Rocket and Vmax generate!

“I’ll have the 72-oz rib eye, please.”

We’re a nation that often embraces the ostentatious – we’re mostly to blame for professional wrestling and competitive eating! – so we figure you’re ready for the main course, to get to the meat of the matter: two over-the-top engines.

An outright leader here depends on your moto value system.

If you’re most enthralled by peak horsepower, then you’ll relish in the fact Big Max’s revvy 1679cc, liquid-cooled, four-valve-per-cylinder, 65-degree, DOHC, V-4 readily hands the Roadster its ass when comparing peak horsepower.

|

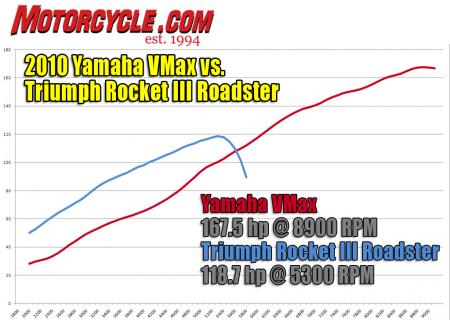

Mad Max managed 167.5 hp at roughly 9000 rpm (Star’s claim is 197 hp at the crank) when we strapped it to the dyno. From this we see why the VMax makes a good platform for a powerful dragster. The power of the Max is the key element behind its allure.

“Its power is nothing short of incredible,” says Kevin of the VMax. He went on to call it a “rubber-burner extraordinaire!”

Mad Max has the potential to post big top speed numbers, but it’s electronically limited to approximately 146 mph. The most sensible answer to this e-nanny is likely an issue of simple aerodynamics. Riding the naked VMax (or just about any unfaired bike for that matter) at higher speeds seems like a frightening, even hazardous prospect. And, well, we do live in a litigious society…

Although respectable by most standards, the Rocket’s best run of a little less than 119 ponies at 5300 rpm simply falls short of the Star’s sportbike-like peak power.

So there ya have it. If you’re looking for a horsepower king, crown Mr. Max.

|

The Rocket III Roadster shows up for the gunfight with a 2.3-liter cannon, a cannon lobbing fat torque bombs at its foe. A peak-torque reading of 136 ft-lbs at 3200 rpm is utterly impressive in its own right, but equally noteworthy is that it twisted out over 118 ft-lbs as early as 1500 rpm. WTF?

Even when the RIII’s peak hp tops out, the Big Triple is still making 117 ft-lbs. Short shift and fuhgeddaboudit!

The Max’s peak 107 ft-lbs at 6700 rpm is nothing to brush off, but in the low-rpm arena the Star’s torque production is shy of the Rocket’s by as much as 55% at some points. And that’s a conservative comparison.

As unique as the power curves are, so too is the character of each engine.

The Roadster’s large flywheel effect is notable as it rocks the bike sideways when the throttle is blipped. It feels as though there’s a deep well of irresistible force lurking in the bowels of the big Triple. Of course the Roadster accelerates with authority, but it does so in a deliberate, linear manner that mirrors its mostly flat torque curve.

The Star’s engine complexion suits the bike’s Mad Max nickname. Like a Jekyll and Hyde, the VMax is as friendly as you like it. But a hideous mad man is only one quick twist of the throttle away.

“Even at low rpm, you can tell there is a brute between your legs. Just a whiff of throttle has major speed implications,” Kevin said with a tinge of fear in his voice (not really).

Indeed, the Max accelerates with the ferocity of most literbikes, as the V-4 spins up much quicker than the Trumpet’s inline. Yet there’s a degree of serenity to the engine thanks to its limited vibration.

On the subject of exhaust notes, the Max reminded Kevin of V-8 at idle, and under power it sounds like a modern, high-performance V-8. The Roadster has a throaty, menacing grumble at idle, too. Pull the trigger and the sound emanating out back is reminiscent of a built truck; like the older Chevy with glasspacks the local kid takes to the Tuesday night drags.

One does it on top, the other on the bottom. Different animals for sure; both big, but different.

|

The Rocket, as expected, can roast the rear tire from a stop, launches hard and will even hoist a sizeable wheelie providing the clutch is finessed just right along with a handful of throttle. But the Max will do the same and then some. Just a little slip of the clutch in second gear and the Star can bake its 200-section rear tire from a rolling start.

Both manufacturers have done a commendable job of mitigating engine vibes.

A V-4 design is inherently smooth running. In the VMax this trait is further enhanced via a contra-rotating balance shaft. Kudos to Triumph, as the big rigid-mount Trumpet Triple is generally free of major buzz, too.

|

More silky smooooveness is located in each bike’s 5-speed gearbox. Shifting action was light and precise on both sleds, although the shorty ASV accessory lever on the Max may have contributed to the sensation extra pull was required.

Good things come in big packages

The VMax brings hi-tech to the table in the form of various engine technologies borrowed from Yamaha’s sportbike line, like YCC-T, YCC-I and the well-known power-enhancing EXUP.

Equally techy is the VMax’s chassis, appropriately updated to match the new V4.

The Max’s skeletal composition boasts a cast-aluminum perimeter-style frame joined to an alloy swingarm; a subframe made of Controlled-Fill cast-aluminum and extruded aluminum pieces completes the package.

We’d expect nothing less for a bike that was some 10 years in the making before its final unveiling. However, for all the VMax’s advanced chassis design it’s not necessarily light years ahead when it comes to real-world riding.

The Rocket’s chassis package is pretty basic cruiser-type stuff compared to the VMax frame.

A twin-spine tubular-steel frame holds the big Triple as a stressed member; the swingarm/shaft-drive housing is also steel. We don’t want to minimize the Rocket’s frame technology, but that’s about all there is to it.

Despite a suspension package (non-adjustable 43mm USD fork and twin coil-over shocks with 5-position ramp-style preload) as no-frills as the frame, the Triumph acquits itself quite well in just about every riding situation you can throw its way.

Considering the limited range of suspension adjustment on the RIII, overall ride quality is descent with sufficient damping.

The Rocket exhibited moderate-to-light steering effort; even low-speed, tight-radius turns are managed with marked ease. Excellent leverage provided by its wide, sweeping handlebar is a big contributor to the friendly handling.

|

For a big, honking, 807-lb sporty cruiser, the newest of the Rockets carries its weight well when hustled down flowing canyon roads where a rider can quickly forget the Roadster rolls a fat 240-section rear tire. Motorcycles with such large rear tires often feel as though they want to right themselves only seconds after initiating a turn. Not so with the Rocket.

The portly Roadster further disguises its heft with a 66.7-inch wheelbase, 32.0-degree rake and 148mm of trail. This is nearly a carbon copy of the VMax’s dimensions save for the Max’s minor advantage of a 1.0-degree steeper steering angle.

Despite the opportunity to finally grace the VMax with fleet-footed steering geometry after all these years, Star (Yamaha) designers and engineers actually made the new Max’s chassis dimensions milder compared to VMax 1.0, as Kevin noted during the 2009 Max’s press launch.

The Roadster’s ability to handle like a motorcycle, say, 100-lbs lighter, is a defining quality of its character, a pleasantly surprising quality at that.

It’s a safe bet the VMax’s aluminum chassis lends considerably to the bike’s middleweight-by-comparison claimed wet weight of 685 pounds. Yet the VMax doesn’t whip ‘round corners as briskly as you might expect.

There isn’t any discernable flex or wallow from the VMax’s stout chassis. However, Kevin noted that chopping the throttle mid-corner occasionally upsets the chassis, a condition he attributes partly to how the Yamaha Chip Controlled-Throttle (YCC-T) affects engine compression braking.

This annoyance aside, the VMax otherwise feels solid and planted, enough that new MO Editor, Jeff Cobb, said he was inspired to routinely drag the VMax’s footpeg feelers during a weekend-long trip up California’s twisty coastline near Big Sur and surrounding areas.

On the flipside, I was surprised at the initial effort required to turn Mr. Max, especially after time aboard the lighter-steering but heavier weight Rocket.

The Max exhibits a falling-into-the-corner sensation. Kevin referred to the feeling as steering “flop.” He also keenly noted the Max’s awkward feeling at low speeds, a trait reflective of what feels like a high CoG on the Star.

We suspect a narrower handlebar compared to the Triumph’s wide bar, and an 18-inch front wheel as opposed to the Rocket’s 17-incher, as culprits that prevent crisper steering on the Star.

Although the VMax lacks sportbike-like handling to mate up to its sportbike-like power, its suspension is polar-opposite of the Roadster’s springy parts.

The VMax’s 52mm fork and solo shock are fully adjustable. A rider benefits further from easily accessed knurled knobs for rebound and compression damping on both the shock and fork. A remote hydraulic adjuster on the bike's left side handles shock preload.

The Star’s ride is better damped overall than what the Rocket offers, but ultimately it’s difficult to get around the rear suspension-altering effects of a shaft drive.

Though shaft-jacking on the Vmax and Roadster’s traditional shaft drive systems isn’t as bad as shaft drives of yore, aggressive acceleration will nevertheless cause the rear suspension to “grow,” just as it does on all shaft final-drive motorcycles. Rear suspension thereby can seem momentarily overly stiff and unforgiving, especially if a handful of throttle is applied.

Braking on either bike is more than sufficient, especially considering the weights and monster power of these big boys.

The VMax wears an impressive-looking set of radial-mount, six-pot calipers clamping down on 320mm wave-type rotors; a Brembo master cylinder is a nice bonus. Braking is aided by the addition of ABS.